VENUS AND CUPID

Rokeby Venus, c. 1647–51. 122cm x 177cm (48in x 49.7in). National Gallery, London.

Rokeby Venus, c. 1647–51. 122cm x 177cm (48in x 49.7in). National Gallery, London.

Rokeby Venus, c. 1647–51. 122cm x 177cm (48in x 49.7in). National Gallery, London.

Pictured: Rokeby Venus, c. 1647–51. 122cm x 177cm (48in x 49.7in). National Gallery, London.

Self-portrait, c.1640

At the time of the Spanish Golden Age, painters were able to produce art work with two major pillars of support, the Catholic Church, and the Crown. “The consequence of painting out of fashion rested solely on having the requirement of painting religious commissions for private or public use. Mythological and historical themes, even allegorical themes were rarely commissioned from Spanish painters in the seventeenth century.” [i] In the seventeenth century, Spanish monarchs were factually famous for being the keen patrons of Spanish artists, as well as having a considerable impact on the establishment of their careers. Diego Velazquez, a Spanish painter from Seville, is undoubtedly one of the more celebrated examples of having a successful relationship with a patron. Velazquez was renowned for doing royal portraits of the king of Spain, Philip IV, and the monarchy’s attendants. Though there is a painting that was painted for an exclusive private audience that never saw the public’s eye for a great portion of its lifetime. Velazquez’s Venus and Cupid (1647-1651), or also known as the Rokeby Venus or Venus at her Mirror, is the only depiction of a nude woman from its time period. This painting has experienced controversy and is often noted as a neglected masterpiece, because works such as this one have been not acceptable to audiences. Back in the seventeenth century, the worse thing than painting a nude was to exhibit them, it simply encouraged lust. The Venus and Cupid is an example of the ideal secretive commission, the public didn’t know of its existence until 1813, which indicates that half of its life had been reached. In the 20th century, this painting is known for its experience of deliberate vandalism at its home in the National Gallery, London. If nudity wasn’t acceptable during this age, then who was the brave model that would commit this outlandish act? (LOL) Where was the artwork produced? What is the reason to make this so hated by many? These rising questions are just the beginning to unlocking the mystery of the painting. The Venus and Cupid is one of the rare treasures of the Baroque period because of its mythological subject matter, rare depiction of a naked woman, and its controversial reputation it has carried into contemporary society.

Born in Seville in 1599, Diego Velazquez launched himself early in his career as one of the most groundbreaking Spanish painters. Coming from what could be described as the "gentry’ class," he developed his natural artistic skills and trained with Francisco Pacheco, who was a locally famous teacher and painter in Seville. History categorizes Diego Velazquez humbly as the royal court painter to King Philip IV. But his career began much before his patronage had begun. Velazquez’s life, before being recognized by the monarchy’s court, rested solely on his education led by Pacheco to becoming one of the greats. His technique is one of the mysteries of his creation. “During the seventeenth century, it was accustomed for all of the painters to use the same materials, materials that tended to be rather simple if not at times crude.” Velazquez is a prime example of this outcome, and the process of trial and error, which ultimately led to the inventive technique of his career. [iii] Going farther along with his technique, it is suggested that he is the type of painter that has an idea for a composition but he would rather see ~ what happens ~ as he works, making adjustments as he paints. Most of his work isn’t exactly detailed to the core, which would make it somewhat fragmented. Unlike many of the other painters from Spain who focused on great detail, grand scale, and prestige, Velazquez proved his simple and quick technique to be successful.

King Philip IV had a reputation for being a fine art collector and having a great eye for talent. Being a sharp judge, he evaluated Velazquez’s work and placed him as the court’s painter, which is a prestigious title he retained for forty years until the time of his death. [iv] His inspirations were limited in Seville. Needless to say, under the Pacheco academy, he developed a commanding style and technique that was spectacularly natural and hardly recognized early in his career. [v] Velazquez mainly produced three types of scenes: domestic life, religious subjects, and portraits. [vi] The foundation of his success lied exclusively on his paintings. Velazquez had the power of portraits, and that's how it took in the interest of the monarchy. Velazquez was fortunate to work with a patron that was a connoisseur of art. It is said that his entry to the court was achieved by his skill as a portraitist. Portraits are defined as images of power and prestige. It was a noble attraction and aristocratic display of the monarchy to the people. Velazquez traveled around Europe to gain a broader understanding of technique, a different opportunity to view subject matter, and a secular understanding of the art world around him.

While working for the king as his royal court painter, Philip IV granted him permission to further study in Italy. Velazquez’s first trip to Italy in 1629-30 was a turning point in the artist’s career as an artist. [vii] He was under severe circumstances with the monarchy, only getting commissioned for portraits. Evidently, that was the theme of the majority of his work during his time with the Spanish crown. Italy exposed Velazquez to a firsthand frontier. During this time his practice underwent a revolutionary change, a change that would be only crucial in the life of any new emerging artist. [viii] As opposed to the conservatism pressured by the Catholic Church in Spain, Italy offered sensuality, full bare anatomy models, and mythological subject matters. Consider all of the horizons Velazquez would have touched, and by being in Italy, which is the pinnacle and beacon of art and architecture, Velazquez had access to view many different mediums of art.

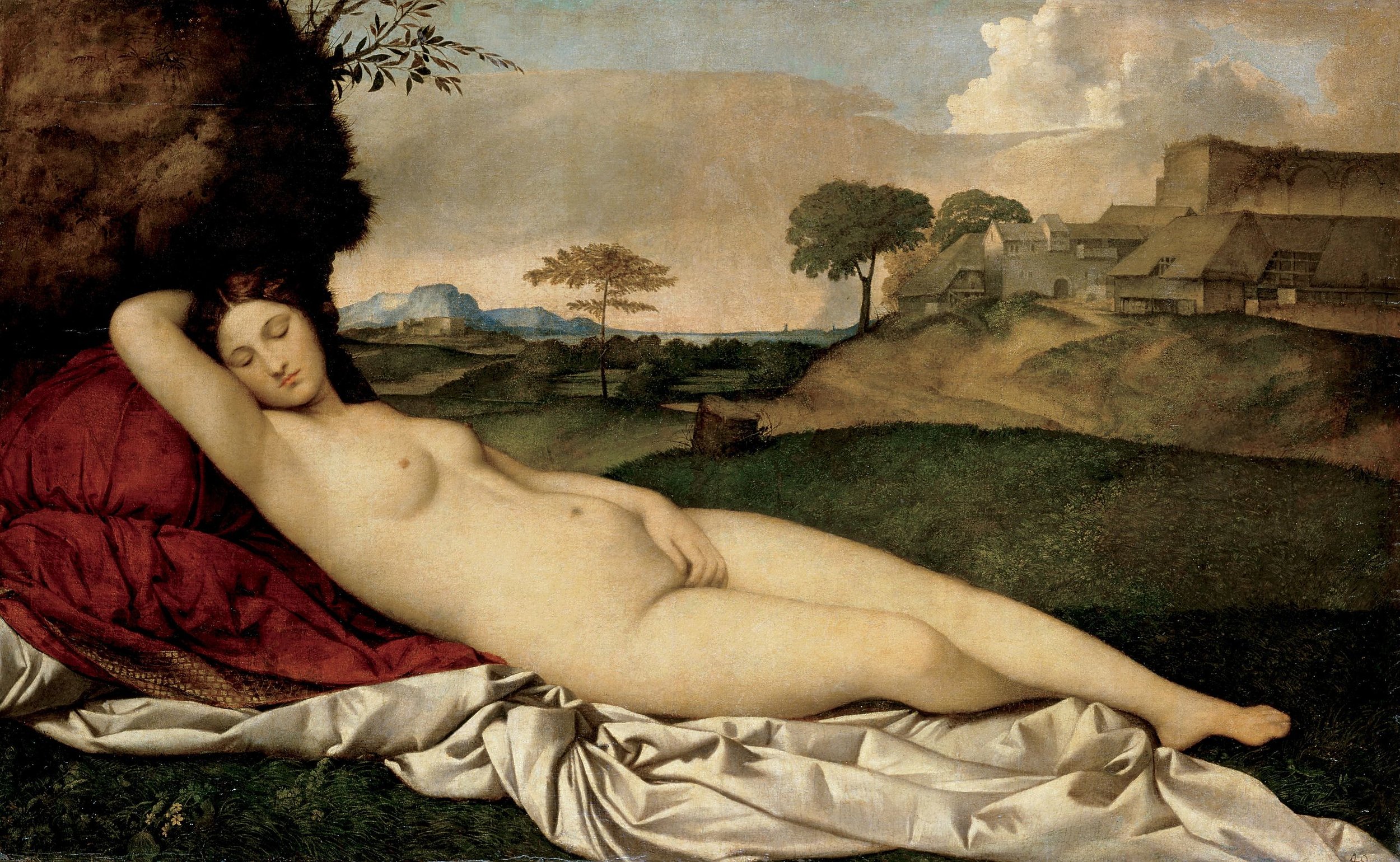

Giorgione, Sleeping Venus, c. 1510.

“Since Velazquez was engaged on a royal mission, he attempted to persuade patrons to give works to the king of Spain and allowed molds to be made of precious antiquities so that copies could be sent back to Madrid.” [ix] One mold that is debated to be the inspiration of the Venus and Cupid is the Borghese Hermaphrodite. The sculpture is an ancient Roman copy that was excavated around 1608-20 and can now be viewed at the Louvre. The reclining position is comparable enough to the swooping backside in Velazquez’s Venus and Cupid. The influence of Italian art on his style is recognizable in the paintings he produced from his time there. Could this be the birthplace of the Venus and Cupid painting? Italy offers so much sensuality, mythology, and ambiguity in real life and in the painting. Though his stylistic influence doesn’t click in Italy, that is the mystery ... it's never been clear where the birthplace of the Venus and Cupid was. Historians know that the painting was painted for a private patron. After researching into the documents of its background, it's now known that Gaspar de Haro, who was a wealthy art collector and also the person who arranged musicals for the royal court, was the first known patron of the piece. [xi] Knowing this would further solve the mystery of the painting’s provenance.

Borghese Hermaphrodite, an ancient Roman copy, excavated c. 1608–20

Venus and Cupid is noted as the best mythological portraits of the seventeenth century not only for Velazquez but also for the entirety of Spanish art. [xii] Venus, the goddess of love and beauty, lounges at her toilet with Cupid, the god of psychical love, who is holding a mirror that displays her reflection. Cupid’s position in the painting is a distinct and vital one. Kneeling towards the right, his profile is the only view of his child-like face, and his arms are extended out holding the mirror towards Venus’ face. Venus was always in high demand in Europe, but specifically by region. One would not have seen this in Spain or any other conservative region because it wouldn’t have been acceptable. Aristocratic men showed interest in the theme all throughout Europe. Obviously. Velazquez was exposed to many nudes, new examples of the human anatomy in sculpture, and to different artists. The body of the goddess meets the viewer with a tremendous impact.

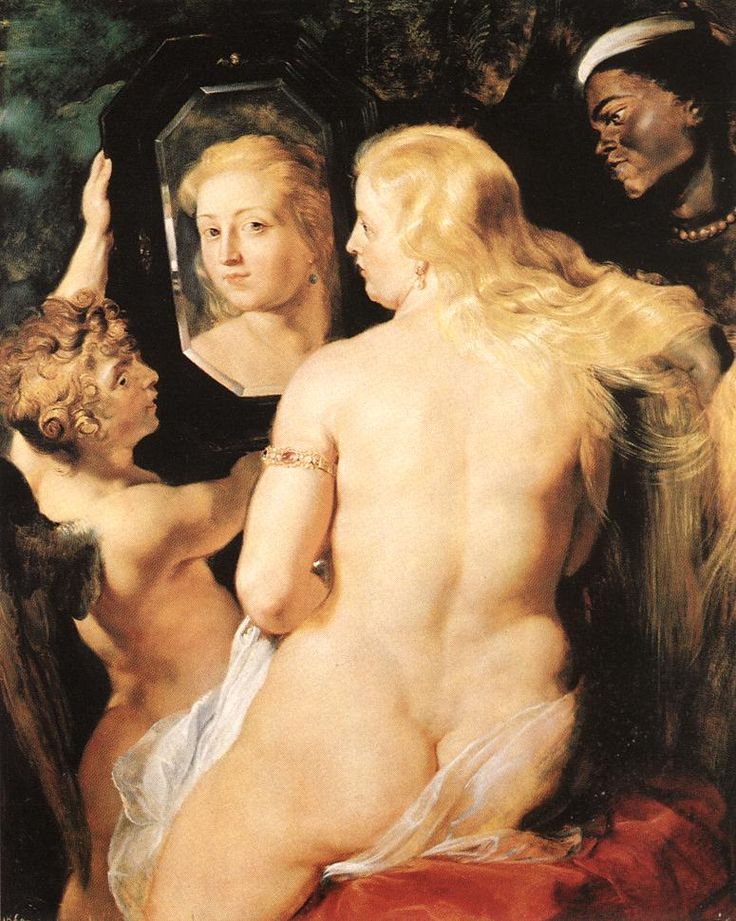

In the composition, it seems that the artist has joined two traditional subjects, Venus at her toilet and the lounging Venetian Venus, to one masterpiece. [xiii] The lounging Venus is commonly displayed throughout the history of art and often painted by a mirror. This female subject goes back all the way to the precedents of Velazquez to Greece and Rome. Velazquez would've had many sources to complete his Venus. Many previously have depicted Venus beautifying herself with the help of her son Cupid. [xiv] It is said that, before Velazquez traveled his way to Italy, “Rubens befriended Velazquez and, although the documents are mute on their relationship, he must have led the Spaniard to a second apprenticeship.” [xv] Rubens opened Velazquez’s eyes to ideas about art that led him to further explore his artistic career and strengthen his subject matter. Other examples of Venus, mirrors, and Cupid are Titian’s Venus at her Mirror [xvi] or Rubens’ Venus at a Mirror. [xvii] Velazquez’s Venus promotes measured desirability. It is a complete view of the body, from a distinct viewpoint. Making its context clear, it was made for its sexuality. It wasn’t "supposed to be shown to the public" and only had one audience, noblemen.

Pictured:

(L) Titian, Venus with a Mirror, 1555

(R) Rubens, Venus at a Mirror, 1615

The mirror is the central mystery of this piece and is essential to the piece’s meaning. Venus’ reflected face seems blurred with no real definition. Exposing only the face and leaving the backside bared it intensifies charged eroticism. By concealing the face, we can assume that Velazquez painfully avoided comparing the Venus to any real woman. [xviii] and hide her identity. Venus has an expressionless face gaze at the viewer. There is a “heightened sense of reality that alters the relationship between the subject and viewer by stimulating the imagination.” [xix] Gavin Ashworth [xx] decided to reciprocate the composition at every detail of the Venus and Cupid. Observations show that if Velazquez followed the laws of composition then the mirror would have revealed the lower abdomen and not the face. [xxi] That would mean that this composition is physically impossible to depict. It isn’t just an image of a nude woman, it has now an effect that only Velazquez would have consciously done. No longer is the priority on Venus, it is now on the viewer, who is just as apart of the scene as those presented. Cupid holds the mirror to show who the woman is but rather expresses psychical love and desire. By featuring Cupid, Velazquez suggests that this was made for lust. He was purposely displaying the women’s face to use as a coy device. Mirrors are often symbolized as many “virtue and vices, including false love, pride, humility, prudence, and/or truth.” [xxii] He uses this reflection, as a symbol that repeatedly reminds the viewers of their own gaze, at the center of the composition. [xxiii] In opposition to the traditional subjects he had been depicting, Velazquez changes his perspective when he establishes his audience. This painting was strictly not for public display, this was made for his or her or their hinted private sexual interests.

Venus and Cupid is a metaphor for desire and temptation. Venus’ invitation is completely alluring. It hazy faded appearance draws the viewer into her beauty so delicately that it has the effect of replacing the controversial focus with what Venus represents, the most beautiful woman in the world. The viewer know she exists in this image, but she knows the viewer exists. Venus’ face is painted to show her gaze on the viewer but is blurred out so viewers can’t distinctly read her emotions. It is a double cleavage effect. The gaze is two sided. By not having the capability of seeing her full body from the front, it is clear that this painting is used as a temptation. Viewers recognizes that she exists as a woman, or rather a goddess, but the thought of who she actually is would have thrilled viewers. Velazquez composes the female form with an unique quality. The curvature and pose are an act of structure. With the tease of desire, viewers "want" her to turn around so the front side would be visible.

Detail of Rokeby Venus, c. 1647–51.

As I stated earlier, what sets Venus and Cupid apart from the others is that it has the quality that electrifies its presence. Velazquez is known for his realistic textures. The glistening flesh gives the painting a satin-texture without necessarily make it perfect. Venetian artists such as Titian are known for the “Venetian color” scheme and charisma. During his time in Italy, Velazquez spent time studying these color effects. By adding a red backdrop against a shadowed background, it adds a sense of sensuality, mystery, and uncertainty of where she is. “Though in spite of the use of dark hues and accents, Velazquez’s Venus does not possess the same structure of light and dark employed by the Venetian artists, nor does it have the “tenebroso” Spanish Baroque painting.” [xxiv] Despite the distorted face, Venus’ body is in great detail. Velazquez paints his Venus against a dark fabric, thus accentuating the swinging arc of her body and rounding the composition. [xxv] He wasn’t trying to capture a portrait, subject or technique he'd been so accustomed to doing. Her body is a soft creamy white that almost completely contrasts the Spanish drapery she is lounging on. Velazquez “rearranges the legs of her body and shows a weightless, restful pose and softens the muscles of her suggestive body.” [xxvi]

Venus and Cupid has the reputation of being a coy image of the Baroque period. Though this painting is known to be obsessively adored by the men it was created for, it isn’t particularly accepted by the feminist attitudes of many women. In 1914, feminist activist Mary Richardson walked into the National Gallery and walked straight to the Velazquez painting and attacked it seven times with a meat cleaver. Though the painting has been fully restored to its successful state, its commonly still known as a victim of an act of protest by a woman. Richardson quotes, “I tried to destroy the most beautiful woman in mythological history because the government tried to destroy the most beautiful women in modern history (Mrs. Pankhurst-a fellow suffragette).” [xxvii] In comparison to the Catholic Church, who would've bashed nudity for being represented, the feminists lashed out too.

“Velazquez’s Venus and Cupid is one of the countless paintings in a long tradition of erotic illusion.” [xxviii] Being a painter of high social status, his skill becomes schematic without sacrificing the realistic tendencies he possesses. This is the result of intellectual evolution. At the end of his career, this painting fires the viewers’ imagination into understanding the mystery Velazquez depicted for his audience. Little is still know about the complete journey of this masterpiece. Historians assume that it was painted in Italy, due to the sensual subject matter, technique and little information about its original patron, Gaspar de Haro. This painting falls under the Baroque period, which was developing into the historical ground-breaking period it is today. Velazquez was not a romantic, sorcerous painter, but rather known simply as a realist. Realism is shown in his portraits and his life-study depictions. Out of all the Venuses ever created, his painting goes perhaps farthest in reminding us of the religious turmoil it has gone through, the patrons it has been tousled around with, and the hidden side of its life, which was held in most of its life, beneath a beautiful and seductive surface. [xxix]

Works and Images Cited:

Brown, Jonathan. Velázquez, painter and courtier. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986.

Brown, Jonathan, Diego Velázquez, and Carmen Garrido. Velázquez: the technique of ] genius. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

Kubler, George, and Martin Soria. "Sources and Interpretation of the Rokeby Venus." In Art and architecture in Spain and Portugal and their American dominions, 1500 to 1800. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1959. 30-37.

Prater, Andreas. Venus at Her Mirror: Velazquez and the Art of Nude Painting. London: Prestel, 2002.

Sutherland Harris, Ann. Seventeenth Century Art & Architecture. 2005. Reprint, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education Inc., 2008.

The Times (New York), "Miss Richardson's Statement," March 11, 1914. http://www.heretical.com/suffrage/1914tms2.html (accessed December 10, 2012).

Tomlinson, Janis A.. From El Greco to Goya: painting in Spain, 1561-1828. New York: H.N. Abrams, 1997.

Velazquez. London: National Gallery, 2006.

Figure 1: Venus and Cupid by Velazquez. 1647-1651. National Gallery, London.

Figure 2: Venus at her Toilet or Venus with a Mirror by Titian. 1555.

Figure 3: Venus at a Mirror by Rubens. 1615.

Figure 4: Reconstruction of Venus and Cupid by Gavin Ashworth

Figure 5: Reclining Nude in a Landscape

Figure 6: Borghese Hermaphrodite, Louvre Museum

Endnotes:

[i] Sutherland Harris

[iii] Jonathon Brown and Carmen Garrido, Velazquez: the Technique of Genius, 15.

[iv] Sutherland Harris

[v] Jonathon Brown, Velazquez: Painter and Courtier, 3.

[vi] Jonathon Brown, Velazquez: Painter and Courtier, 7.

[vii] Jonathon Brown, Velazquez: Painter and Courtier, 69.

[viii] Jonathon Brown, Velazquez: Painter and Courtier, 71.

[ix] Janis Tomlinson, From El Greco to Goya, 100.

[xi] Velazquez. London: National Gallery, 2006.

[xii] Jonathon Brown, Velazquez: Painter and Courtier, 182.

[xiii] Jonathon Brown, Velazquez: Painter and Courtier, 182.

[xiv] Martin S. Soria, Sources and Interpretation of the Rokeby Venus, 36.

[xv] Jonathon Brown and Carmen Garrido, Velazquez: the Technique of Genius, 10.

[xviii] Jonathon Brown, Velazquez: Painter and Courtier, 183.

[xix] Jonathon Brown, Velazquez: Painter and Courtier, 182.

[xxii] Martin S. Soria, Sources and Interpretation of the Rokeby Venus, 37.

xii Andreas Prater, Venus at her Mirror, 9.

xiii Andreas Prater, Venus at her Mirror, 85.

[xxv] Martin S. Soria, Sources and Interpretation of the Rokeby Venus, 35.

[xxvi] Martin S. Soria, Sources and Interpretation of the Rokeby Venus, 35.

[xxvii] Miss Richardson's Statement” by the Times (New York)

[xxviii] Andreas Prater, Venus at her Mirror, 120.

[xxix] Martin S. Soria, Sources and Interpretation of the Rokeby Venus, 37.